THE Boggs Academy

John Lawrence Phelps, Founder of Boggs Academy

The history of Boggs Academy is intrinsically woven into the lives of families in Burke County, Georgia, as well as into the mission and witness of the Presbyterian Church. Much of this story begins with the little-known history of Moses Walker, a white landowner who fathered thirteen children with two enslaved women. One woman bore seven sons, the other four daughters and two sons. After emancipation, Walker gave land to his children, creating the Walker Settlement—a two-square-mile community along Quaker Road.

From these families emerged two streams of worshippers: one Presbyterian, the other Baptist. The Baptists established Noah’s Ark Church, while the Presbyterians organized Morgan Grove Presbyterian Church in 1906, on land donated by Morgan Walker. After a fire destroyed the original sanctuary, it was rebuilt as the John I. Blackburn Church, which still stands on the Boggs Academy campus today.

In 1906, Dr. John Lawrence Phelps recognized the need for education in this community. With land donated by Mrs. Emiline Walker through her son Morgan, the first two acres of Boggs Academy were established. The Presbyterian Church’s Board of Freedmen, led by Virginia Boggs, raised funds to construct two simple frame buildings—one for worship and schooling, the other for the principal’s home. What began beneath a brush arbor with fewer than ten pupils became a school that would change generations.

Over the decades, Boggs Academy grew from a local Sunday school into a prestigious boarding school for African American students. By the 1940s and 1950s, Boggs offered general, commercial, and vocational tracks, with a vibrant campus life filled with academics, athletics, music, and service. Families from across the nation entrusted their children to Boggs: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s niece, Hosea Williams’s daughters, and even the grandsons of U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond all studied here.

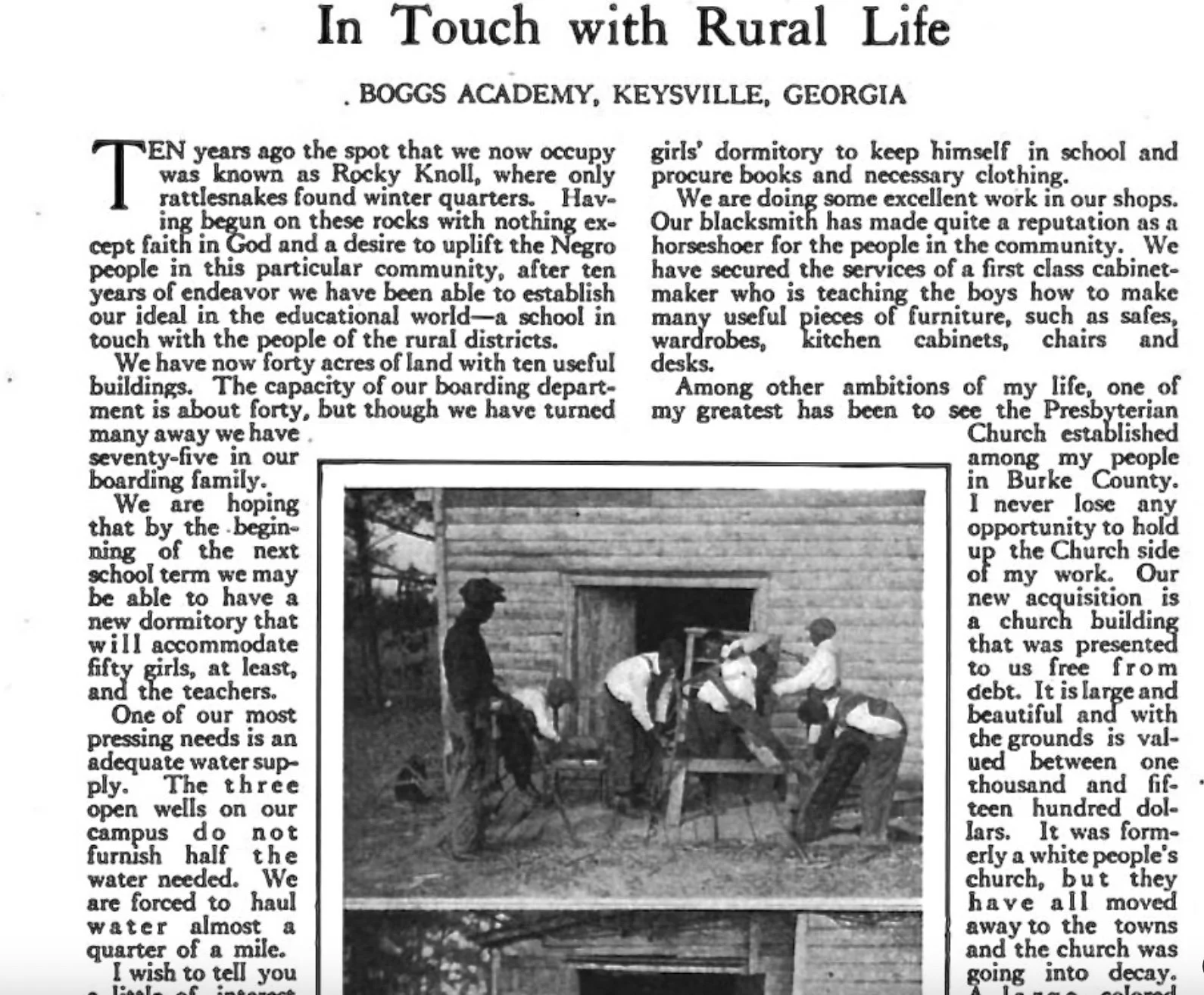

In its earliest years, Boggs offered grades one through six, with the mission of giving the boys and girls of the community an opportunity to improve themselves mentally and morally and to make themselves useful and substantial citizens. Over time, the school transitioned into a full high school, with more and more students boarding on campus.

By 1940, the boarding population was steadily growing, and in 1955 the school developed three tracks: general, commercial, and vocational education. Extracurricular activities included athletics, the a cappella choir, newspaper, photography, science club, and Boy Scouts. The “Boggs Program” consisted of four parts—study, worship, work, and play—built on the principle of Christian Purpose, Preparation, and Performance. The Boggs student body originally came from the rural sections of Georgia and were both “unchurched and unschooled,” but in time, students came from other parts of the state and other states also. Ninety-five percent of the graduates went on to colleges, which ranged from Ivy League schools such as Dartmouth College to Morehouse in Atlanta and Howard University in Washington, D.C.

In 1986, Boggs Academy closed its doors due to declining enrollment, a drop influenced by the shifting tides of integration between 1978 and 1983. Like many institutions that served Black rural communities, Boggs faced systemic disinvestment. In 1984, the academy graduated its final class. Yet the legacy never died. In the hearts of alumni and believers across the nation, Boggs remained a spiritual and cultural landmark. In 1991, the school’s legacy was reborn as the Boggs Rural Life Center, Inc. (BRLC), a nonprofit dedicated to carrying forward Boggs’ vision of education, leadership, and community uplift. Today, on the very grounds where brush arbors once sheltered eager students, BRLC continues to steward a bold legacy with a BIG vision for a future worth fighting for!

Beside Every Great Man!

Mary Rice Phelps, wife of the Boggs Academy Founder.

Mary Rice was born on May 1, 1867, in Union County, South Carolina, to Adeline and Hilliard Rice. A gifted learner from the start, she could read by the age of four and began formal schooling at just five years old.

By the time she was thirteen, her talents as an educator were already apparent. With her parents’ blessing, Mary took the teachers’ examination, earned her certificate, and was placed in charge of a large school in Spartanburg County. After a year of leading that school, her parents insisted she continue her own education—a decision that would shape the rest of her life.

Mary studied first at Benedict Institute in Columbia, South Carolina, then entered Scotia Seminary (now Barbara Scotia College) in Concord, North Carolina, in 1881, graduating in 1885. Her career advanced quickly. She served as principal of the public schools in Glenn Springs, South Carolina, for three years before being elected assistant principal of the Eddy School in Milledgeville, Georgia, in 1890.

On October 25, 1891, she married John L. Phelps in Helena, South Carolina. Two years later, she was elected assistant principal of Cleveland Academy, but soon left to join the Haines Industrial School in Augusta, Georgia—a pioneering institution dedicated to educating African American youth. Even during her school-year responsibilities, Mary spent her vacations teaching rural children, determined to reach those with the fewest opportunities.

Mary Rice Phelps was not only a teacher but also a writer and thought leader. Her essay, The Responsibility of Women as Teachers, was featured in James T. Haley’s Afro-American Encyclopedia (1895). In it, she urged mothers to embrace their role as their children’s first teachers, instilling moral character and values from the earliest years.

Her life’s work was rooted in the belief that education was both a right and a responsibility—one that could transform lives and communities.

Mary Rice Phelps passed away on October 9, 1931, in Keysville, Burke County, Georgia, at the age of 64. Her influence, however, lives on in the generations of students and educators she inspired.

Lela Stone, founding president Boggs Community Development Cooperation

Emma Gresham, former Keysville’s Mayor

Boggs Rural Life Center, Inc

The story of the Boggs Rural Life Center,Inc. is one of determination, community action, and a refusal to let legacy die. In the late 1980s, when Boggs Academy closed its doors, there was a real risk that its vast land and powerful legacy would be lost or sold off. But the surrounding community refused to let that happen.

It was through the leadership of the Boggs Community Development Corporation (BCDC), in partnership with Keysville Concerned Citizens (KCC) and the Burke County Improvement Association (BCIA), that the vision for Boggs Rural Life Center, Inc. (BRLC) took shape. Together, these grassroots organizations represented decades of civil rights advocacy, civic leadership, and educational progress in Burke County and beyond. And at the center of their efforts were two women and a brother who embodied the spirit of transformation.

Mrs. Lela Stone, a lifelong educator and founding president of BCDC, had served as a teacher, administrator, and school board member in Burke County. She understood that land, education, and opportunity were inseparable—and that Boggs was worth fighting for.

Mrs. Emma Gresham, a retired teacher and community advocate, returned to Keysville to find basic public services denied to Black residents. Her fight for water and sewer access led to the discovery that the town had quietly been disenfranchised for more than 30 years. Through relentless organizing and legal action, she revived Keysville’s city government and was elected its mayor in 1989, along with five Black city council members.

Mr. Herman Lodge, the founding president of BCIA, made national history. In 1967, he filed suit against the Burke County Commission to challenge its at-large voting system, which had systematically prevented African Americans from being elected to public office. The case, Lodge v. Rogers, ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1982—and the court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. That decision became a landmark victory for voting rights and is widely considered one of the most significant political civil rights cases of the 20th century. It helped reform district voting practices across the country.

Boggs Community Development Corporation led the initial efforts by Boggs Academy Alumnus to-reopen Boggs shortly after the closure in 1884. After several years of fruitless work, BCDC in 1989 south to employ a new strategy to save Boggs. Under the auspices of there John L. Phelps Parish, BCDC organized a collaborative effort to preserve Boggs involving the National Boggs Alumni Association, the National Black Presbyterian Caucus, Keysville Concerned Citizens (KCC), and the Burke County Improvement Association (BCIA).

With support from Rev. John L. Phelps Parish, BCDC brought together a powerful coalition—including the National Boggs Alumni Association, the National Black Presbyterian Caucus, KCC, and BCIA. Their shared goal: to keep Boggs alive as a “beacon of hope to the disenfranchised and underdeveloped African American communities of the Central Savannah River District.”

What followed was a hard-fought, 8-year campaign to stop the sale of the land. The coalition filed legal action, petitioned the Presbyterian Church, and held prayer vigils on church steps to demand the transfer of the property to local control. During this time, the 24 buildings on the 1,232-acre campus—dormitories, faculty housing, classrooms, cafeteria, library, gym, and pool—sat unused, waiting for revival.

Then, a breakthrough. In 1990, the Sapelo Island Research Foundation provided critical support with over $160,000 in grants. That funding helped pave the way for negotiations, and in June 1991, the Presbyterian Church formally conveyed the property in full ownership to the newly formed Boggs Rural Life Center, Inc.

Since that moment, Boggs Rural Life Center has grown into more than a place—it has become a platform. A platform for land & agricultural stewardship, rural education, leadership development, and cultural restoration. It continues to honor its original mission by creating opportunities for the underserved and underrepresented people of the region.

The BRLC story is not just about preservation. It's about power—community power. It's about what can happen when citizens fight for their place, their land, and their future.